Developing countries whose economies depend on commodities must enhance their technological capacities to escape the trap that leaves most of their populations poor and vulnerable, says UNCTAD’s Commodities and Development Report 2021, published on 7 July.

About two thirds of developing countries were commodity dependent in 2019, meaning at least 60% of their merchandise export revenues came from primary goods, such as cacao, coffee, copper, cotton, lithium and oil.

The report, “Escaping from the commodity dependence trap through technology and innovation”, highlights the correlation between low technological capacities and high commodity dependence.

It warns that most of the 85 commodity-dependent developing countries (CDDCs) will remain trapped for the foreseeable future unless they go through “a process of technology-enabled structural transformation”.

Commodity trap must not be seen as fate

About 95% of countries that were commodity dependent in 1995 remained so in 2018, according to the report.

“Commodity dependence is a state that’s hard to change,” UNCTAD Acting Secretary-General Isabelle Durant said, “but it must not be seen as fate.”

“If developing countries embrace new technologies and innovation, and receive the right support from the international community, they can transform and use their resource wealth for better outcomes.”

Ms. Durant said building technological capacities must be a priority as CDDCs try to recover from the COVID-19 crisis, and that the current high prices of many commodities should not encourage these countries to “produce more of the same”.

“Otherwise, these nations and their populations will be just as vulnerable to the next shock as they were to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic.”

The odds are stacked

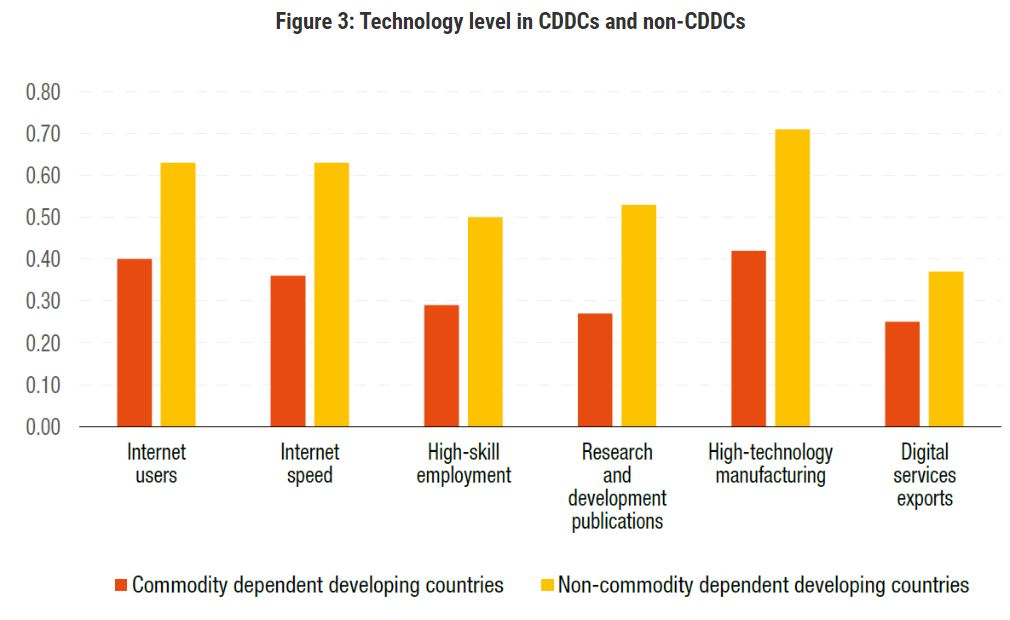

The report’s analysis shows the odds of commodity dependence are strongly associated with low levels of technology.

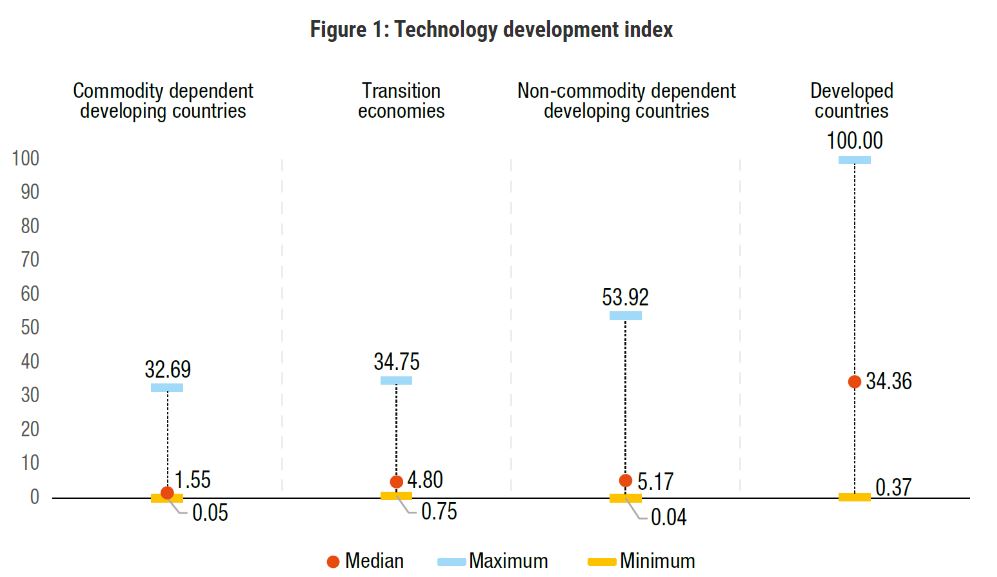

For example, in the Technology Development Index presented in the report, CDDC’s median score is 1.55 compared with 5.17 for developing countries that are not commodity dependent (non-CDDCs), such as China, India, Mexico, Turkey and Viet Nam.

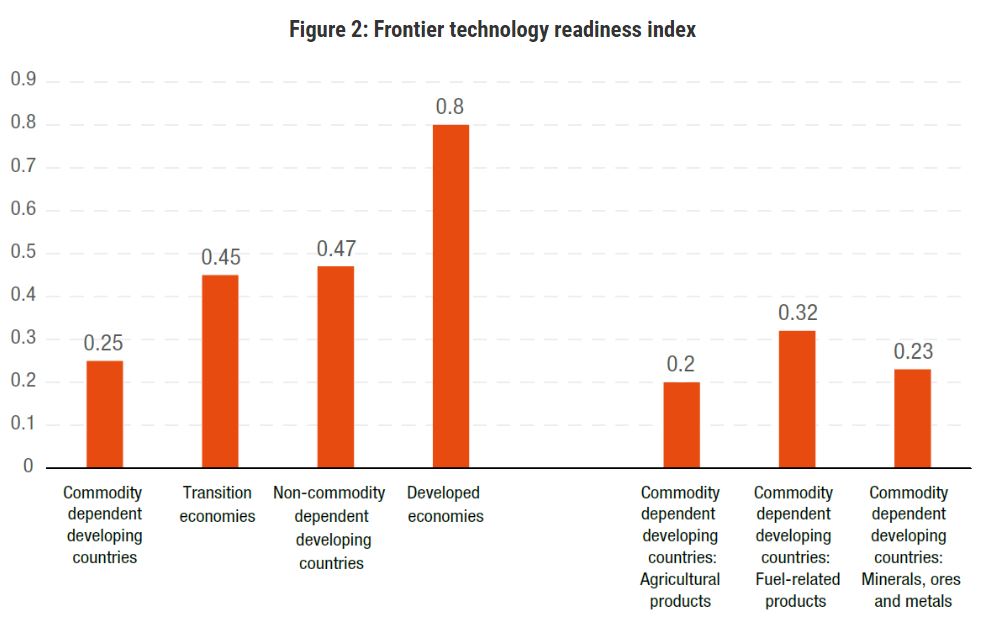

Another index in the report, on frontier technology readiness, paints a similar picture. CDDCs, whose median score is 0.25, are less prepared than non-CDDCs (0.47) to use technologies such as artificial intelligence, the internet of things, blockchain and robotics.

In a business-as-usual scenario, the report calculates it would take the average commodity-dependent country 190 years to reduce by half the difference between its current share of commodities in total merchandise exports and that of the average non-commodity-dependent country.

But some countries have shown how to overcome the odds.

From coffee and bananas to microcircuits

In 1965, food commodities represented 83% of Costa Rica’s total merchandise exports. Coffee and bananas alone accounted for about 68%, compared with just 7% for manufactured goods.

But four decades later, the country’s export basket had dramatically changed. The food sector’s share had dropped to 24%, and the main export had become electronic microcircuits (26% of total merchandise exports), followed by machine parts and accessories (15%).

The Central American nation’s path to export diversification, the report says, was enabled by a policy environment supportive of the technology, innovation and human capital needed first to diversify into higher-value food products, such as fruit juice, and then to establish and grow high-tech sectors.

Other success stories include Indonesia’s transformation from oil dependence to processed goods, Malaysia’s diversification from rubber and palm oil towards manufactured products, such as tires and medical gloves, and Botswana’s move up the diamond value chain.

A government-led process

One factor common to all the successful cases, the report says, is the active role governments played “in bringing about a strong commitment to change from the status quo and putting in place the resources needed to move forward”.

Strong political will and a long-term vision is crucial because technology-enabled structural transformation takes decades, and many challenges must be overcome.

These include an abundance of manual labour with low levels of digital skills, limited IT infrastructure, few public and private resources to fund research and innovation, and stringent intellectual property protection that poses barriers to the wide diffusion of technological know-how.

Designing and implementing science, technology and innovation policies should be the business of the whole of government, the report says, as different ministries and agencies will be engaged in the work necessary to build a supportive ecosystem.

This includes improving hard infrastructure, such as reliable electricity and internet connections, and soft infrastructure, such as rules and regulations that govern innovation and technology adoption. It also implies setting up institutions of research and development and achieving macroeconomic stability.

Guided by national development plans

Technology-enabled structural transformation should be realistic and guided by national development plans, objectives and priorities.

The report recommends identifying new sectors that are close in the current national production space and then designing targeted policies to promote innovation, either by improving the product or the process of production.

Governments will have to work with the main actors of national innovation systems, including firms, research centres, universities and financial institutions.

Technology transfer to avoid dead ends

Diversifying into more dynamic sectors might require CDDCs to take “large jumps” in innovation, and the report says some of the technologies needed will have to be learned or transferred from abroad.

“It is essential that international public and private partners of commodity-dependent developing countries facilitate technology transfer and participate in commodity-dependent developing country efforts towards building the physical, human and institutional capabilities required for the adoption and domestication of the relevant technologies,” it says.

Technology transfer is critical because of the “unconnected” nature of producing commodities.

“They are like dead ends,” the report says. “Once a country is in a particular product space, it is difficult to use the capabilities therein to move to another product.”

For example, Angola’s technology capacities, which are highly concentrated around petroleum extraction, are not easily transferable to new sectors like digital services.

The process of technology transfer should be adapted to local contexts and could be financed through special funds created for this purpose, as is the case with the Paris Agreement, according to the report.

It says: “If the Paris Agreement were to be the model framework, developed countries would be required to provide and report on technology transfer and capacity-building support to commodity-dependent developing countries, based on the needs assessment of each commodity-dependent developing country.”

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)