Drewry’s latest Container Forecaster report includes huge upgrades for freight rates and carrier profits as market faces extended period of under supply.

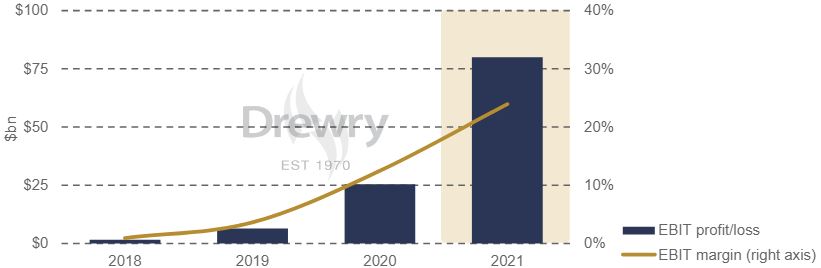

The latest edition of Drewry’s Container Forecaster finds that 2021 will be the first year in the history of container shipping when carrier profits approach $100 billion and average freight rates jump by 50%, against a background of huge operational disruptions to the port and ship systems.

Many of the themes covered in the latest edition will be familiar. Port congestion and equipment availability challenges, for example, have not gone away and continue to drive market prices, but what is different from three months ago is that some of the numbers are much bigger.

The latest edition, published on 30 June, includes a relatively small forecast upgrade for world port throughput in 2021-22, but significantly inflated outlooks for freight rates and carrier profits over the same period.

Volumes are expected to continue to rise through the 3Q21 peak season and to end the year with annual growth of approximately 10%. There will still be growth next year, but probably only about half as strong as consumer spending is expected to move back towards services as Covid-related restrictions are lifted.

The containership fleet is not growing fast enough to meet insatiable demand right now. A scarcity of open charter fixtures means that some lines are scouring the second-hand market for expensive new assets to add to the pile, but others can only supplement with newbuild deliveries, or are simply having to make do with what they have.

Source: Drewry Maritime Research

Cautious newbuild contracting of recent years means that we expect the cellular fleet to only increase by 4.2% this year and 2.8% in 2022, in both cases significantly below that of world port throughput projections.

Appetite for new tonnage has accelerated since 2H20 and in less than six full months this year’s contracting activity is already close to the record 2.7 million teu placed in 2007.

Drewry maintains the view that high levels of newbuild contracting for 2023 pose a risk of overcapacity returning to the market during that year, but future supply requirements are heavily clouded by new environment regulations due to become law at the start of 2023, that may or may not see significant chunks of the containership fleet slowdown in order to comply.

This edition contains a special summary analysis of the action points from the June IMO MEPC76 meeting as well as some of the potential pathways for the industry to meet the decarbonisation targets.

The big change to our forecasts comes from our freight rate and profitability outlooks. Box shipping rates reached new highs in 2Q21 as spot rates continued to surge and contract pricing followed suit. At the moment it is hard to predict when prices will peak as worsening supply-chain disruption continues to stoke pricing on a weekly basis.

We are now getting accustomed to seeing triple-digit annual growth rates for spot rates on most lanes. That these instances are no longer shocking is further proof, if needed, that the market truly is crazy right now.

Average freight rates (spot and contract) across global trades are expected to rise by around 50% in 2021, an uplift of as much as 30% on our March forecast, indicative of the acceleration in pricing seen already through 1H21.

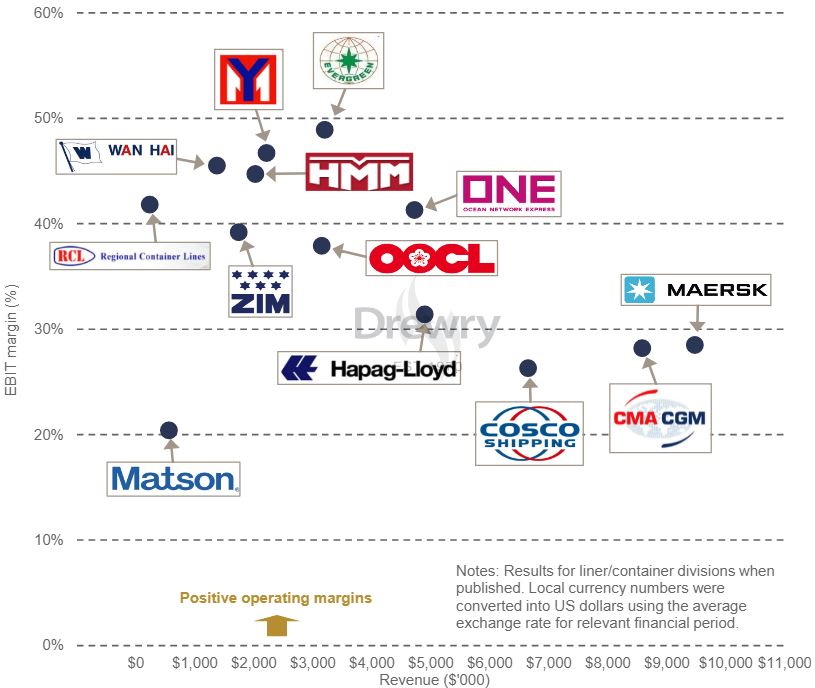

The extreme increases in freight rates have naturally translated into blockbusting carrier profits. Carriers posted a record EBIT result in 1Q21 of $27.1 billion, up from what now looks a miniscule $1.6bn in same period one year ago. So impressive are the latest quarterly results, they even eclipsed the full-year 2020 EBIT of $25.4bn.

Source: Drewry Maritime Research, derived from ocean carrier financial reports

Given the substantially higher freight rate forecast for this year, Drewry has made a major upgrade to our full-year 2021 industry EBIT outlook. We are now forecasting industry EBIT of approximately $80 billion for this year – up from our previous estimate of $35bn. If freight rates surpass expectations in the remainder of the year, we would not be surprised to see an annual profit line in the region of $100bn.

For 2022, we expect EBIT to drop by a bit more than one-third due to softening freight rates and rising costs that may stay higher for longer with many carriers locking into expensive longer-term charter fixtures. Nonetheless, it would represent another astonishing performance by historical standards.

Regrettably, Drewry is less optimistic about a solution being found to fix the supply chain disruption and thinks the market is facing medium-term (or extended) under-supply. Events at the South China port of Yantian (a Covid-19 outbreak in May hobbled operations for nearly a month, with knock-on congestion at nearby ports in Asia), and earlier in the Suez Canal, demonstrate just how fragile the container shipping eco-system is and how challenging it is to try and build in more resilience.

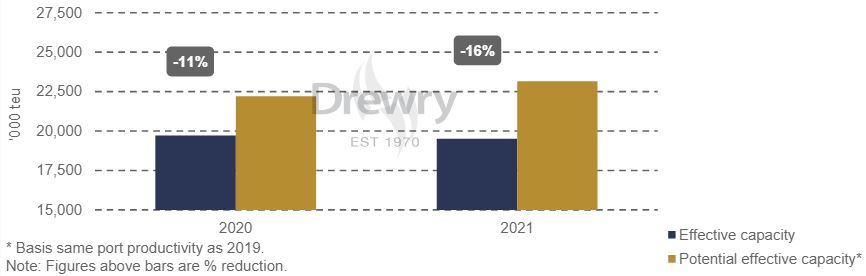

Source: Drewry Maritime Research

Supply side disruption has become the key driver of freight rates and remains the top sensitivity to our forecasts. Drewry now thinks lower port productivity will continue into 2022.

Subsequently, Drewry expects the Global supply-demand index to average 105.7 in 2021, up 0.9 points on our previous assessment. Any reading above 100 indicates tightness of supply in the market.

Drewry estimates that 16% of worldwide effective capacity (the slots available to the market) will have been lost this year as direct consequence of lower port productivity, following on from an 11% reduction last year.

In an alternative reality when Covid-19 did not damage port operations and productivity was maintained at 2019-levels the Global Supply-Demand Index would have averaged only 84.0 in 2020 and 89.0 this year. That timeline is not seeing the record freight rates and carrier profits we are experiencing.

These are some of the factors required to fix the supply chain and get containers flowing as they should, in our view:

• Port productivity needs to improve – dependent on avoiding Covid outbreaks and for less liner service disruption

• More reliable and predictable liner services to give ports a better chance to clear the backlog – likely dependent on improved port productivity

• A slowdown in Asia to US demand to promote more equal distribution of capacity and equipment

As you can see, this is something of a circular problem. Shipping lines alone do not have the power to fix things, but the industry at large somehow needs to find a way to break the vicious circle.

Source: Drewry Maritime Research

Our view

Even if carriers do revert to type and the current newbuild craze ends the upcycle in 2023, they will have made so much money between 2020-22 that they will be set up for years to come. They could potentially make as much profit in this window as they could have hoped in a decade, or more.

Carriers’ only account in deficit is public relations. With increasing attention on shipping’s environmental footprint and tax contributions, lines are in danger of being cast as profiteering villains, unsympathetic to the needs of their customers. We hope they will be good global citizens and do more to help improve the efficiency of the supply chain.

Source: Drewry