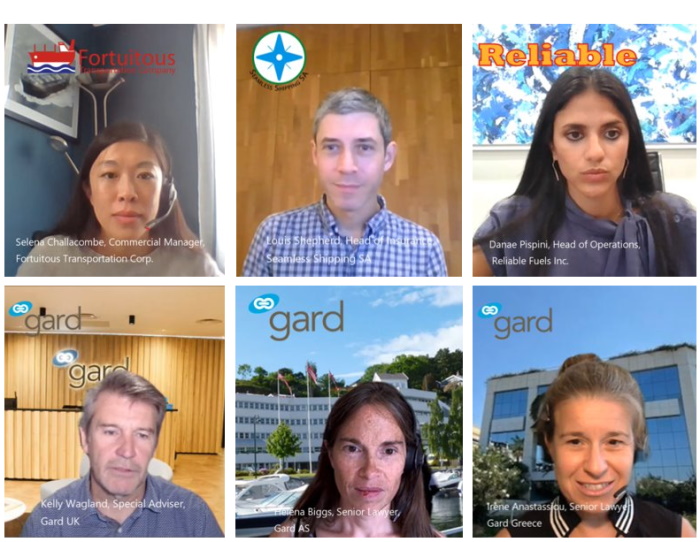

At the webinar, we considered conflict issues, off-spec bunkers and what happens to bills of lading when cargo is transhipped. We also looked at how our new Gard internal dispute resolution procedure for conflict cases works. We tried to approach this in a novel way that gives the members an idea of how we deal with conflict cases in real life. After the details of the scenario were set out, the audience was a “fly on the wall” during various telephone conversations between the members (owners, charterers and sub-charterers), each member and their claims handler, and the claims handlers amongst themselves. We saw the action unfold from the parties’ point of view from an initial main engine breakdown through the transhipment and delivery of the cargo at its destination, to a final discussion between the claims handlers on how the various disputes could be resolved with the help of a Gard internal mediator. For those unable to attend, a video of the webinar can be view here.

In this article, we follow up on the questions put to the panel members (who played the part of the different interests within the scenario) some of which we were unable to answer on the day due to time constraints.

Question: In a Defence case involving two or more Members and clients, how do you make sure that communications are kept confidential on a practical level?

Answer: In the Defence and Charterers and Traders’ teams, we have two practical ways of maintaining confidentiality. First, different Teams are instructed to handle the files which means that there is a physical layer of insulation between the two new claims handlers to avoid the risk of people inadvertently disclosing confidential information, for example, by overhearing conversations or picking up documents and messages. Secondly, the IT system has a functionality to enable people to “lock” files so that only specific individuals are able to access conflict files, both in terms of electronic document management systems and also in terms of the claims database. So, if someone without permissions looked at the highest level of available information, it would show an empty file or nil estimate. This helps to maintain confidentiality and to avoid people seeing any information which might indicate how the claims handler perceived the risk of liability.

Question: Could the Sub-charterers actually claim such large losses under the sale contract?

Answer: In the scenario, the cargo of fuel was bound for a resort destination where it would be used to generate power. The sale contract entered into by the voyage charterer had penalty provisions for late delivery due to the needs of the receiver. The engine difficulties meant delay and triggered the penalty provisions and the sub-charterer intended to claim these penalties from the time charterer and Head Owner. A claim could certainly be made for the losses, but the question of whether the claim would succeed is more difficult to answer. Obviously, the result would depend on what the particular contract terms were and, in this case, we did not have any of the relevant details.

Nevertheless, broadly speaking, there are likely to be two key areas that would need investigation. First, was there a breach of charter which would entitle the sub-charterers to bring a claim for damages? A vessel may be unseaworthy if she only has un-usable fuel on board, but the duty to provide a seaworthy vessel is normally one of due diligence only, so there may be issues around whether or not the fuel problem should have been identified or mitigated earlier. If the problem was not with the fuel, but with the handling, then that is more likely to pave the way for a claim against owners/disponent owners.

Secondly, under English law, a claimant can generally only recover damages under a contract if they were reasonably foreseeable at the time of contracting. Here, the owners/disponent owners seem to have been quite surprised to discover the potentially high losses that would arise for each day of delay which raises the question of whether these were losses of a type that was reasonably foreseeable. Further, whilst English law recognises the concept of liquidated damages, punitive penalties are generally not recoverable. That said, there is always some litigation risk, and with such potentially high losses and correspondingly large claims, it does look sensible of the parties to act in a way that minimised the issues, making it easier to resolve.

Question: I have been in the situation where a problem with the bunkers has been discovered only after the time bar in the supply contract has expired. What can the purchaser of the bunkers do in those cases?

Answer: This scenario is not that unusual in practice. The difficulty is that the operational analysis only tests for predefined criteria, but sometimes, where there are components which are not covered by the operational analysis, the handling characteristics of the bunkers only become apparent once they are put into use. Many bunker supply contracts have very short notice periods, such as 7 or 14 days from the date of delivery. Where the contractual notice period has already expired when problems start to manifest themselves, as a matter of good practice, it is worth giving notice as soon as possible.

In situations where the bunker fuel is causing operational problems but has tested on-spec under the ISO standard, further testing of the bunkers, such as GCMS (Gas Chromatography Mass Spectroscopy) testing, may demonstrate that there are chemicals in the fuel which should not be present. However, that often takes time in itself and if there is a serious problem in the market, such as the 2018 Houston fuel problem, there may be issues with laboratory capacity which introduce more delay. Whether giving notice after the expiry of the contractual notice period will be effective or not will depend on the law of the supply contract, but at least giving notice keeps those arguments live whereas if no notice is giving, then the purchaser is giving up any potential claim.

Question: What is the status of the bunker analysis received after testing? How can there be any dispute?

Answer: Whether the bunker analysis is binding in terms of determining whether the bunkers are off-specification will depend on the terms of the charterparty and the scope of the analysis. In the charterparty, the parties will usually have agreed that the bunkers need to meet a certain ISO standard and the bunkers are tested for substances for which limits have been set by that standard. The scope of the operational analysis tends to be reasonably narrow in terms of the predefined criteria, so it does not produce a comprehensive profile of the chemical composition of the fuel. As a result, it is possible to have bunkers which are confirmed to be ISO compliant on the basis of the operational testing, but which contain other more esoteric chemicals which cause operational problems. In this regard, there is a catch-all provision in ISO 8217 in clause 5.3 that the fuel should be “free of any material that renders a fuel unacceptable for use in marine applications” so if there are other problematic chemicals which create a risk of damage to the engine or mean the fuel cannot be handled onboard the ship, further testing, such as GCMS, might be required to demonstrate a breach of this clause of the ISO standard.

Investigative testing will not necessarily show up certain types of problems such as fuel instability. If more extensive analysis results do not point towards a clear breach of the relevant ISO standard, a final layer of protection can often be read into the charterparty as a matter of law. Whilst this will depend on what the applicable law is, many statutory regimes have a requirement that goods which are supplied are fit for purpose, i.e. in the context of bunkers, they must be suitable for consumption. If it can be shown that the bunkers cannot be safely consumed, even if the chemical reason for their unsuitability cannot be pinpointed, this may still entitle shipowners to reject bunkers or claim damages. So, in summary, bunker analysis results are not necessarily determinative of quality issues.

Question: Why is no-one talking about general average? Isn’t this a general average situation?

Answer: General average arises where there is a voluntary sacrifice or an extraordinary expenditure incurred to deal with a common risk, preserve property and complete the contractual voyage. Customarily, the loss of expenditure will be shared between the interested parties on a proportionate basis. In the present scenario, it was not a question of incurring costs so as to preserve property at risk or to complete the voyage, i.e. ship, cargo, bunkers etc. It was anticipated that the ship could complete the voyage after repair with only a relatively short delay, but the costs were incurred so as to get the cargo to the island as quickly as possible. In other words, there were commercial considerations in place that led to the transshipment of the cargo to another vessel rather than the inability of the vessel to proceed and deliver her cargo.

Question: As far as I know to be a GA case the cargo needs to be in danger as well (like cooled cargo) but in this case the cargo is not in danger. To face a GA case the 5 check points need all to be fulfilled (as per my understanding)

Answer: Parties to a voyage commonly agree to the application of the York-Antwerp Rules if a general average situation develops. Rule A of the York-Antwerp Rules states “There is a general average act when, and only when, any extra-ordinary sacrifice or expenditure is intentionally and reasonably made or incurred for the common safety for the purpose of preserving from peril the property involved in a common maritime adventure …”. If Rule A is broken down, there are five essential and key features within the Rule which must be satisfied in order to validly declare general average:

• The sacrifice or expenditure must be extraordinary; and

• The sacrifice or expenditure must be intentional; and

• The sacrifice or expenditure must be reasonable; and

• The general average act is for the common safety; and

• The general average act must be for the common maritime adventure.

In the current example, the ship and the cargo were not in any imminent danger, and the reasons for the transhipment were purely commercial considerations. As such general average did not arise.

Question: Can an external mediator be appointed but otherwise Gard procedure for informal intervention be followed?

Answer: In essence, the answer is yes. The mediator would be required to agree to conduct the mediation in accordance with Gard’s mediation framework which we would expect to be acceptable. Whereas Gard provides mediators without charge to Members, appointing an external mediator would inevitably lead to the generation of some costs which would have to be shared between the parties. The costs of the external mediator are subject to the Defence policy terms.

Question: Would a Gard internal mediation be expensive to run?

Answer: A Gard mediation would be less expensive to run than an external mediation since there is no charge for the mediator. Mediation can generally be expensive because lawyers are often used to prepare the case summary, the disclosure and to attend the ‘mediation’ which is usually a physical meeting lasting one day, involving each party and the mediator, at a venue to be agreed. These elements plus the cost of the mediator can mean that mediation can be quite expensive.

In addition to saving the costs of the mediator, one of the benefits of a Gard internal mediation is that these costs can be reduced. The idea is that the Gard internal mediation will assist the parties using Gard’s internal resources. External lawyers may be appointed, but under the Gard procedure they would not communicate directly with the Gard mediator or represent the member at the mediation meeting itself. This is likely to streamline the associated costs substantially. In addition, building on working practices developed in response to the pandemic, it would be possible, if the parties agree, to deal with a Gard mediation remotely which would save legal and management costs of travelling to a venue and meeting there for one day. We would hope that most Gard internal mediations will be inexpensive to run.

Question: Presumably Owners and Head Charterers would appoint their own engineering experts both in anticipation of litigation but also to provide advice to the respective members. Is this correct?

Answer: Yes, this type of case requires expert assistance. Often, where there are main engine issues, the H&M underwriters will have someone in attendance and the P&I or Defence Clubs (as appropriate) will often join in the appointment to ensure that evidence is gathered and preserved, but the scope of the engineering input would almost certainly go beyond the immediate response. Even if the working hypothesis is that there is a problem with the bunkers, an expert marine engineer can comment on the onboard handling of the fuel and whether the problems experienced might have been caused by the fuel.

When a case is live, expert marine engineers can also advise on whether there is anything the crew can do to mitigate potential losses. Equally, the parties would probably also need expert chemists to look at the fuel’s chemistry. The analysis reports are very technical and so an expert would be needed to interpret the results and advise on whether the fuel was on-specification and whether any mitigation steps were possible, such as the use of additives to deal with any handling issues. If there is nothing obviously wrong with the fuel, a chemist can also advise on what other tests should be done. With the increase of bunker claims in recent years there are several firms with considerable expertise in this area.

Question: One of the important factors that often emerges during the refuelling operations of the ships is the sampling of the fuel supplied. Although the regulations (see MARPOL) clearly state that the sampling point should be the ship manifold, suppliers often claim to have the manifold barge as a sampling point. Often the samples may not represent the true quality of the bunker provided.

Answer: Whilst MARPOL Annex VI sets out the procedure for where and how samples should be taken and how they are handled, the procedure only applies to the MARPOL sample. A few jurisdictions, like Singapore, require the bunker supplier to take samples at the ship’s manifold and charterparties will often define the manifold sample as the relevant sample for quality disputes. However, bunker suppliers commonly have terms and conditions specifying that only a sample taken at the barge’s manifold will be representative for the purpose of any quality dispute.

The different approaches introduce a risk of inconsistent results between the ship and barge manifold samples. If bunker purchasers cannot align the relevant contractual terms, they can still take practical steps to manage the risk, such as having a representative present during any sampling, whether at the ship’s manifold or the barge’s, with all parties signing and sealing samples in the presence of each other. If the bunkers have not been co-mingled on board, further samples can also be draw from the tanks to help exclude the possibility of onboard contamination although it is sensible to instruct an expert to advise how samples should be drawn from the tanks as disputes can arise in relation to the methodology.

If the evidence across the three sets of samples discussed above points to the bunkers being non-compliant or having off-specification parameters, the purchaser is likely to be in a stronger position to engage with the bunker suppliers to address the quality dispute.

Question: Is it expected in this kind of issue to have a joint survey performed to shed some light on the cause of the vessel engine failure?

Answer: Wherever there is a significant main engine breakdown which is likely to put the vessel out of service for an extended time, it is recommended that experts or surveyors attend the vessel to assess the breakdown, identify the steps and timeline needed to rectify the breakdown and to gather evidence to assess cause and liability for the respective clients. Each party would appoint their own expert or surveyor, but in reality, any inspection is likely to take place jointly. It is good practice to ensure that surveyors are accompanied whilst onboard anyway and it means that the facts are more likely to be agreed, even if different people have different interpretations.

Even if the survey is carried out jointly, the surveyors or experts should not agree to any joint conclusions but should report back to their clients confidentially. In addition, any testing is best undertaken on a joint basis with an agreed protocol to ensure transparency of results and avoid disputes about the testing methodology at a later stage. Whilst Charterers may have the right to copies of log books, documentary requests generally have to be routed through Owners’ office rather than dealt with on the ground to ensure that everyone is clear about what documents have been provided and what documents remain outstanding.

Question: If there is a technical problem on the vessel, she will be off hire under the t/c party and in addition to that are also the owners exposed to additional claim from the Time Charter?

Answer: Off-hire is a contractual remedy so a vessel can only be placed off-hire if the incident is a qualifying event for the purposes of an off-hire clause. If there is no such contractual provision or the off-hire clause is not triggered by the incident, there is no right to place the vessel off-hire. Instead, the charterer will need to demonstrate that the owners were in breach of a particular clause in the charterparty (such as failure to maintain the ship) in order to claim their losses as damages. The scope of the damages claim will depend on the nature of the breach and what defences owners typically have in standard charterparties (such as defences afforded to owners by Hague or Hague-Visby Rules), as well as whether the losses were foreseeable and within the contemplation of the parties.

It is worth noting that if the off-hire incident arose out of a breach by the charterer, for example, because they provided off-specification bunkers, the off-hire clause could not be relied upon by the Charterers since the loss of time was caused by something that they were responsible for. For this reason, surveys and expert involvement at the outset are extremely important to ascertain the cause of the breakdown and the issue of liability.

A few concluding remarks

The handling of conflicts tends to be a sensitive subject and we hope that we have provided an insight into Gard’s approach and the processes we follow to ensure that our Members and clients’ confidentiality remains protected at all times. Beyond the ease of access to the other party’s P&I or Defence Club, there are a number of internal dispute resolution procedures which have been developed with the aim of creating additional value where the parties to a dispute have entries with Gard and turning a potential conflicts situation into an added benefit for our assureds..

For more information about Gard’s internal alternative dispute resolution options in conflict cases, please contact your regular Defence or Charterers and Traders claims handler. For more information and recommendations regarding bunker quality disputes, please see our Gard Insight articles: Contaminated bunkers – protecting the purchaser and Bunker supply contracts – key considerations for the buyer

We thank all of those who took the time to attend our webinar and those within our organisation who supported us in producing the session.

Source: GARD https://www.gard.no/go/target/32372876/