Grain and soya trade has grown briskly during the past two years but recent expansion has mainly reflected much higher grain imports into China. What are the prospects for global trade and related bulk carrier employment in the year ahead?

Rising import demand in a number of countries has been a feature of world grain and soya trade during the past couple of years. Movements are mostly seaborne, with benefits for long-haul bulk carrier employment. A large part of the extra volumes seen was comprised of China’s expanding requirements. While tentative signs have suggested that the upwards global trend could continue, doubts have arisen, reflected in diverging views about the outlook.

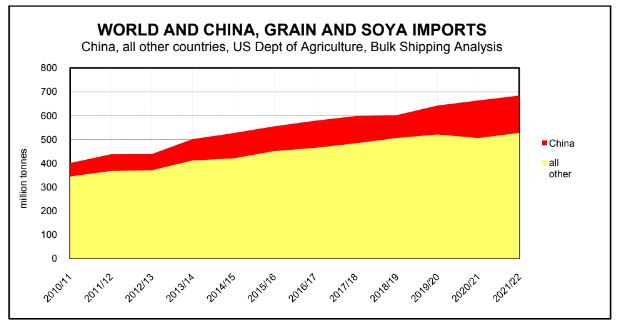

Annual world trade in wheat and coarse grains plus soyabeans and meal has increased by just under two-thirds in the past decade. The total grew by 263 million tonnes, from 400mt in the 2010/11 trade year, to an estimated 663mt in 2021/22, according to calculations based on US Department of Agriculture data. Annual average growth was 5.2%. After a minimal increase in 2018/19, the past two trade years saw a strong performance, assisted by resumed expansion of both grain and soyabeans imports into China.

Cereals and oilseeds consumption trends in many countries around the world remained robust during the past decade. In particular it is evident that consumption generally was well supported in the past eighteen months, amid the coronavirus pandemic and its adverse effects on economic activity. An unpredictable influence, continuously affecting grain import demand, is the varying effects of weather on domestic production of crops in many countries which are active importers. As a result, trade forecasts in both the short and longer term are often somewhat speculative.

Import trends

The trade volumes shown in the first graph include wheat, coarse grains (mainly corn, also sorghum, barley, oats and rye) plus soyabeans and soyameal. For coarse grains and soya, about 70% of the total, the trade year used by USDA is October/September, starting 1 October and ending 30 September. For wheat, the remaining 30%, the trade year is July/June, starting 1 July and ending 30 June.

After averaging 6.8% annual expansion in the first five years of the past decade, from 2011/12 to 2015/16, global grain and soya trade growth decelerated in the next five years, 2016/17 to 2020/21, to an average 3.7% annually. Three years ago, in 2018/19 there was a sharp slowing to only 0.7% minimal growth. Then a rebound followed in the next year, 2019/20, when the highest growth rate for six years at 6.7% was seen. In the latest 2020/21 year which ended last month (September), a slowing to a 3.3% estimated increase occurred.

At first glance the 10% overall increase in world grain and soya trade seen in the past two years is a remarkable outcome. It suggests that the broad upwards trend is being solidly maintained, and has encouraged expectations of further enlargement. But more detailed analysis reveals that this performance has been chiefly influenced by the upturn in China’s imports.

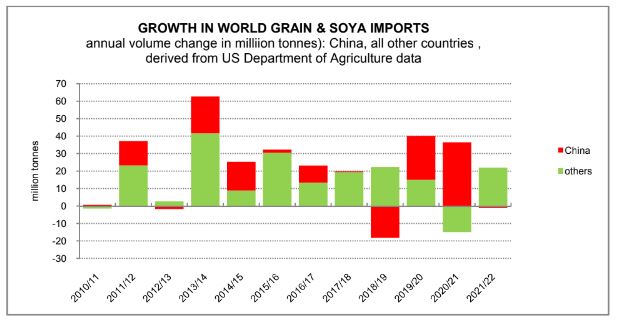

This feature is clearly illustrated by the second graph, showing annual changes in grain and soya import volumes for (a) China and for (b) all other importing countries together. Imports into China now comprise 24% of the world total, an advance of ten percentage points, from a 14% share of world trade at the beginning of the past decade.

Focusing on the most recent events, three years ago in 2018/19 there was a large 16% reduction in China’s grain and soya imports to 96.3mt following almost continuous growth over many years. Two rapid annual expansions have been seen since then, by 26% to 121.4mt in 2019/20, and by 30% to 157.9mt in 2020/21. That performance contrasts with imports by all other countries. These were 5% higher in 2018/19 at 505.9mt, and rose by another 3% to 520.8mt in 2019/20, before falling back by 3% to an estimated 505.6mt in 2020/21.

Changes in the past three years

What explains these contrasting changes? In 2018/19 the reduction in China’s imports mainly reflected a downturn in soyabeans purchases caused by a severe animal disease outbreak, African Swine Fever. This disease spread widely and decimated pig (swine) herds and other livestock, in turn reducing feed usage within which soyameal is a key ingredient. During that year soya imports into other countries rose. Imports of grain into China also decreased, while among other countries there was growth in grain import demand. The outcome, as illustrated in the graph, was that China’s reduction was more than offset by other countries’ net increase.

During the next year, 2019/20, a broadly positive pattern evolved. China’s imports of soya rebounded as the disease outbreak receded and livestock feed production revived, while a tightening domestic grain market boosted wheat and coarse grains purchases. Overall imports into China increased by 25.2mt. Elsewhere around the world, including other Asian countries, the Middle East and African countries, more imported grain and soya was needed. Consequently global grain and soya imports rose by 40.1mt (7%) based on Bulk Shipping Analysis calculations derived from USDA data, reaching 642.3mt.

In the 2020/21 trade year just ended, world grain and soya trade increased at a slower pace than seen in the preceding twelve months, reflecting a noticeably different pattern among importers. China, as the graph shows, raised grain and soya imports by 36.5mt. This expansion was mainly caused by a big increase in corn purchases, accompanied by higher volumes of wheat, barley and other grains, amid declining stocks and tightness in the domestic market. Conversely grain imports into numerous other countries weakened, resulting in global grain and soya trade growth slowing to 21.3mt (3%) at 663.5mt.

Differing forecasts for 2021/22

Another sharp contrast between changes in imports into China, and those into the ‘other countries’ category, is expected during the new 2021/22 trade year starting this month. According to Bulk Shipping Analysis calculations using several separate USDA forecasts published on 12 October, global grain and soya trade could continue its upwards trend. The total may increase by 20.8mt or 3%, reaching 684.3mt.

But China is not expected to contribute to this forecast expansion. Imports into China are estimated to essentially flatten. While soyabeans imports may increase by 2mt to reach 101mt, grain imports may decrease by 3.1mt to 55.7mt, resulting in a marginal 0.7% reduction in the overall China total to 156.8mt. Other countries together are expected to see expansion resuming, more than reversing the previous year’s downturn, with a 22mt rise. The outcome foreseen is a global trade increase reflecting additional demand in a number of countries, including the Middle East area and European Union, but excluding China.

Contrasting in part with this positive outlook was a forecast published on 23 September by the International Grains Council. IGC analysts suggest that China’s wheat and coarse grains imports could see a decline of more than one-fifth in 2021/22 to 47mt. Increases among other countries could provide a partial offset, resulting in global wheat and coarse grains trade decreasing by 3% to 416mt. But comparison with USDA’s estimates is not exact, because IGC measure all grain trade movements in a July to June year, while USDA use this period for only the wheat element.

A forecast by the Food and Agriculture Organization also highlights expectations of reduced global wheat and coarse grains trade. Bulk Shipping Analysis calculations based on data included in FAO’s quarterly report published on 23 September show a decline of 2% to 417mt in this trade, during the July 2021/June 2022 year. A detailed breakdown by importing area or country is not provided in the report.

USDA’s perspective on grain imports into China, in trade year 2021/22, is more nuanced than suggested by the official forecast mentioned above of a limited decrease. In a report published on 30 September, the department’s agricultural experts based in Beijing concluded that corn and sorghum imports, the largest component, are likely to fall by almost one quarter, while wheat and barley imports decline by over a sixth, reducing the total for these four grains by 21% from just over 60mt in the past twelve months. Incorporating such a lower estimate of China’s grain imports implies a less positive view of prospects for world grain and soya trade as a whole.

Uncertainties surrounding future volumes

One uncertainty has receded, at least until mid-2022. Grain import demand is mainly located in the northern hemisphere, where domestic harvests in many importing countries occur in the June-September period. The resulting crop quantity, and also quality – potentially a significant aspect – of 2021 harvests are now known, so the estimated implications for import demand of any changes this year are already incorporated in 2021/22 trade forecasts.

The impact of changes in broad economic trends on grain and soya consumption and import demand usually is less immediate than on dry bulk commodities related to industrial activity – manufacturing and construction. But the covid pandemic and related control measures implemented by governments around the world, starting in early 2020, had a devastating impact on economic activity, well beyond effects seen in normal cyclical slowing phases. Although the resulting exceptionally severe global recession experienced last year had clear potential for extending negative impulses into food and feed commodities, cereals and oilseeds usage mostly remained firm.

Among clear signs of positive influences likely to affect trade in the 2021/22 year, grain and soya imports into the Middle East region could see an upturn after weakening in the past twelve months. USDA calculations point to regional volume rising by almost 8mt (11%), to 78.2mt, mainly reflecting additional wheat and coarse grains quantities. In particular, purchases by Turkey are likely to be much higher, after a domestic harvest shortfall this summer.

Probably the biggest uncertainty among importers in the twelve months ahead, with negative implications, is the prospects for China’s purchases. USDA’s formal expectation that imports of grain and soya by Chinese buyers will be largely maintained around the elevated level seen in the past twelve months seems optimistic. Other analysts are not convinced, seeing a proportion of the past year’s growth as an exceptional boost which may not be sustained. The sharp downturn in China’s wheat and coarse grains purchases foreseen by the IGC recognises this possibility.

Several influences may ease the tightness in China’s grain market over the year ahead, resulting in lower imports. Domestic production in this summer’s harvest was raised by 15mt to 417mt, a 4% increase. A proportion of the recently enlarged imports may have been utilised to stabilise inventories, preventing more de-stocking after reported earlier reductions. Further diversion of wheat and corn into livestock feed could be restrained.

Predicting the volume imported by China always involves guesses, partly because reliable data on some aspects – for example grain stocks, regarded as a state secret – is not available. Moreover, for many other countries, predicting import volumes is not a straightforward task, even where adequate statistical evidence about the most significant influences is available. When forecast adjustments emerge these often seem to mainly reflect actual patterns of current purchases in the market, rather than being based solidly on underlying demand/supply.

Bulk carriers in the kamsarmax, panamax, supramax and handysize segments of the world fleet obtain substantial employment in the grain and soya trades. The share of these trades in global dry bulk commodity trade volume is estimated to exceed 10%. But the share of tonne-miles – a more useful measure of employment significance – appears to be around 15%. Coupled with the effects of often extended port loading and discharging activities, causing longer overall voyage duration, and also the variable impact of seasonal fluctuations, changing grain and soya employment remains a focus of freight market attention.

Forecasts of global grain and soya trade can provide only a guide to what seems the most likely outcome, based on an incomplete picture of influences. For the 2021/22 year ahead current signs, reflecting assessments of import demand around the world, point to potential for a weakening after the strong performance seen in the past two trade years.

Source: Article for Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide by Richard Scott, managing director, Bulk Shipping Analysis; visiting lecturer, London universities