A good working relationship with the pilot, effective Master Pilot Information Exchange at the start of the pilotage followed by well performing Bridge Resource Management during the pilotage passage, are important factors in a successful pilotage.

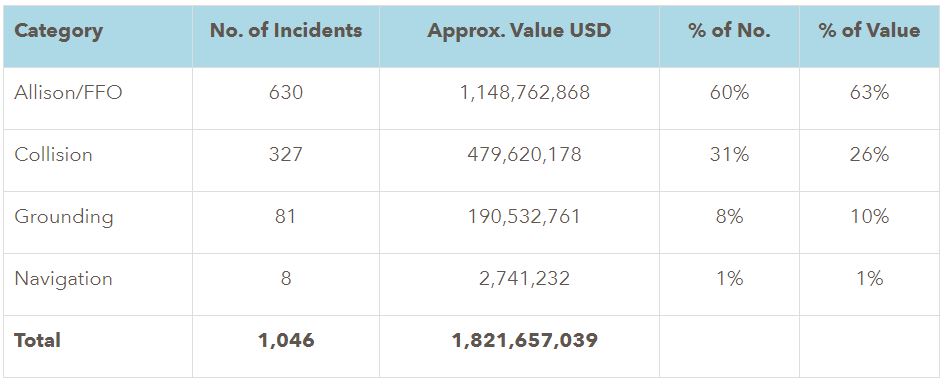

In December 2020 the International Group of P&I Clubs (IG) issued its report on P&I claims involving vessels under pilotage covering the 20 years from 1999 to 2019. During this period there were some 1,046 incidents where pilot error contributed to or caused an incident. Total cost of these incidents was over USD 1.8 billion. Whilst there is volatility both in number and severity of the incidents in each year, the annual average of 52 incidents equates to one incident per week, and the average value per incident is approximately USD 1.7 million.

The report considers incidents in four categories. As can be seen from the table above, incidents in the Allision/FFO category represent the majority, constituting approximately 60% in terms of both number and value. This is to be expected since pilots are most frequently onboard to assist a vessel with its arrival at or departure from a berth. Collision incidents, those incidents which involve contact with another vessel, is the second largest category, representing approximately 30% in terms of both number and value. Given the circumstances required for a grounding to occur, the frequency of these incidents at about four per year is, as expected, much lower than that for incidents in the Allision/FFO and Collision categories. However, the average value of grounding incidents – USD 2.35 million – is the highest of all the four categories. It is also worth noting that 25% of all grounding incidents occurred in the Suez Canal. As for claims in the Navigation category, these are claims arising from the wash of the vessel under pilotage, and the number of incidents and their overall cost is relatively small.

How to make the most of all available resources on the bridge

It is often apparent when reviewing the circumstances of incidents generating P&I liabilities that have arisen when vessels are under pilotage, that the Bridge Resource Management (BRM) on the vessel has been sub-optimal. When accidents occur whilst a vessel is under pilotage, the cause is generally a collective under-performance of the bridge team, and it is recognised that the ships’ masters and officers will also have played a part. Consequently, the IG report recognises the importance to safe navigation under pilotage of an effective Master-Pilot Information Exchange (MPX) at the commencement of the pilotage, and good BRM during the pilotage passage. The need to reinforce training in these areas is emphasised and that this training should focus on matters such as:

• Proper and diligent MPX, and ensuring that pilots are fully informed about any limitations of the vessel’s machinery or equipment, e.g. engine power, steering, bitt capacity etc.

• Understanding all aspects of the voyage plan for the passage under pilotage.

• The need for vigilance on the part of the ships’ officers in monitoring the progress of the vessel with reference to that plan.

• Officers raising the awareness immediately when any deviation from the passage plan is noted

• Communication with the pilot – especially when there are doubts.

• Encouraging officers to question a pilot where there is any uncertainty about the situation or the actions intended, and understanding the most effective way in which to do this.

• Reinforcing the understanding of masters that, with the sole exception of the Panama Canal, the pilot directs the navigation of the ship, supported by the bridge team. The master remains in command and has the right, and indeed the duty, to intervene if it should be felt that the actions of a pilot endanger the safety of the ship.

One key ingredient to the establishment of an effective bridge team when under pilotage is the creation of a good working relationship with the pilot from the outset. The pilot’s relationship with those on the vessel they have been rostered to assist begins during the process of boarding. That is a hazardous operation with an ever-present and real risk of personal injury to the pilot.

Gard’s perspective

In today’s busy world, especially on ships, there is little time to stop and think about potential problems, and to ask “what if…?”. There are response plans and checklists available for emergency situations which have the clear potential to cause the crew and ship harm – for example, steering gear failure and fire. However, many serious incidents start life when there is no emergency as such, and only develop into emergencies because the potential for harm has not been foreseen or has been considered too remote. Instead of asking ourselves “what if…?” we tend to persuade ourselves that something bad will not happen. In the wider context, asking “what if…?” is very much a part of situational awareness.

The development of BRM has done much to address deficiencies in situational awareness, by stressing the importance of a team approach. However, if members of the bridge team are too preoccupied with the tasks at hand, or other human factors, such as fatigue, are at play, there will be a much greater likelihood of potential emergencies not being considered at all.

Drawing on Gard’s experience of casualties we can offer the following observations on how to improve safety on board ships:

• focus on team and leadership training to develop a trusting and open culture on board with a “speak up” environment,

• conduct BRM training more frequently and improved familiarisation with equipment on board,

• share experiences and lessons learned from incidents through workshops attended by both ship’s officers and onshore personnel – the practice of merely sending out company alerts and notifications about incidents is of limited effect,

• shipowners’ top management should take an active part in group work sessions and safety discussions during company conferences and training workshops,

• have a crew on board who can communicate effectively in English between themselves and with others,

• avoid single watch-keeping operated ships and have the master on the bridge when operating within port limits and confined waters,

• do not disable equipment alarms and pay attention to them when triggered, and

• ensure compliance with STCW, particularly in terms of safe/appropriate manning and hours of rest.

Source: Gard, https://www.gard.no/web/updates/content/31992372/pilot-on-the-bridge