The town of Wayne, W.Va., near the Kentucky border, knows something about transitioning coal workers to clean energy jobs. The non-profit Coalfield Development, housed in a retrofitted five-and-dime brick store downtown, has already retrained more than 1,400 people for jobs in industries with a more promising future than coal.

“Construction has been our most reliable job-creation sector, but we’re seeing a significant increase in solar installer jobs as well,” said Brandon Dennison, who founded Coalfield Development a decade ago to try to revitalize southern West Virginia mining towns. “We have 30-60 people on our waiting list at any given time wanting to sign up.”

Organizations like Dennison’s are ground zero in the massive energy transition set to accelerate if U.S. President Joe Biden delivers on his goal to decarbonize the nation’s grid by 2035. The push to revitalize coal communities and create new jobs will only succeed by engaging with people where they live, Biden administration officials said.

However, whether workers in small coal towns across Appalachia, New Mexico and Wyoming will actually benefit from clean energy manufacturing opportunities that may surface hundreds of miles away is unclear. As is whether the billions in federal funding about to be injected into coal-dependent regions can be the economic development catalyst hoped for by many.

“Those are the hard questions we’re trying to tackle,” said Brian Anderson, executive director of President Biden’s Interagency Working Group on Coal and Power Plant Communities and Economic Revitalization. “The core problem is that we can’t really find a replacement for high-paying coal mining jobs without transforming the whole economy.”

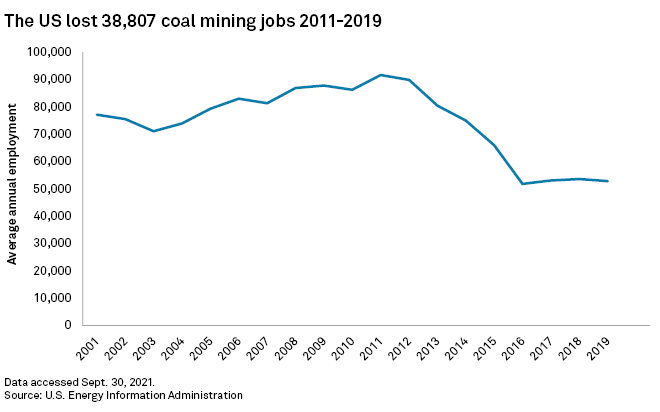

Democratic policy proposals seeking to deliver on the Biden administration’s science-driven climate change agenda, if successful, would gradually eliminate several hundred thousand fossil fuel jobs. In return, another 3 million jobs could be created in efforts to develop renewable, energy efficiency and future technologies like green hydrogen, according to often-cited estimates by University of Massachusetts economists.

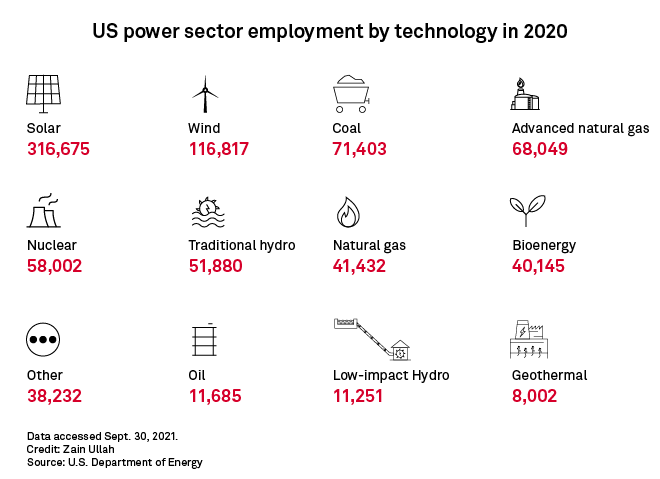

Such energy industry changes would speed up a shift that that has been underway for years. In 2020, more than twice as many Americans worked in solar and wind-powered electric generation than in coal and natural gas, the government’s most recent U.S. Energy and Employment Report shows.

Anderson pointed to Ford Motor Co.’s Sept. 27 announcement that it will invest $11.4 billion in new electric vehicle and battery manufacturing facilities in Kentucky and Tennessee as examples of such transformational change. Those projects will generate some 11,000 jobs, Ford said. Another example is a June announcement by a Morgantown, W.Va., steel plant that it received an order for 1,600 tons of steel components for the first U.S. offshore wind turbine vessel, Anderson said.

“That’s … exactly the type of the type of transformational jobs that we’re targeting,” Anderson said.

And yet, those announcements may not do much for the former coal workers on Coalfield Development’s waiting list. Steel of West Virginia Inc., the plant with the vessel order, has not indicated that its new contract will result in more hiring. And the nearest Ford EV plant in Kentucky, when opening in 2025, will be a four-hour drive away.

“Policymakers often aim to replace old energy jobs with ‘new energy’ jobs, but this strategy won’t work everywhere,” said Ben Cahill, a senior fellow with the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “Not every coal community has the solar radiation or wind resources required for renewables to be competitive. We need to be realistic and not seek ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions.”

Coal country may offer certain economic advantages, Cahill noted, such as natural landscapes that attract tourists or good rail links that can support new industry. But workers will have to be retrained with new skills and experience to qualify for jobs in the new energy economy. Few jobs in the renewables industry, for example, are open to people with no prior solar or wind experience.

To bridge such gaps, the Biden administration’s “whole-of-government” approach to revitalizing coal communities involves the U.S. Labor Department, U.S. Education Department and other agencies focused on training and employment.

Coal regions vying for investments

The Interagency Working Group on Coal and Power Plant Communities and Economic Revitalization has identified 25 coal-dependent communities across the U.S. as especially vulnerable. In more than 90 mostly virtual meetings held so far with people in such priority locations, Anderson said any solutions clearly must be tailored for regional and local conditions.

“We’re not singularly focused on the energy sector,” Anderson emphasized. “We’re certainly casting a wide net.”

Coalfield Development is among dozens of organizations vying for the first round of Build Back Better Regional Challenge grants, a $1 billion community revitalization program funded by the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief spending package that President Biden signed into law in March.

And more money is headed into communities hit hard by the energy transition away from coal. The interagency group stands ready to disburse another $38 billion to help coal mining and plant communities move on.

Dennison is applying for a $67 million grant to expand solar installations for businesses across southern West Virginia and reclamation of former mines. The Coalfield Development founder hopes that the money will also help spawn new local businesses.

“For the last 10 years we’ve been doing this on a shoestring,” Dennison said. “This is a chance to take what we’ve proven works and to really scale it up, to truly transform our economy.”

Virtually all who become trainees with Coalfield Development and are later placed in a job are either former coal workers or people who have difficulty finding employment in economically depressed communities in West Virginia. Some are recovering from opioid addiction, which has ravaged the state, especially in the southern counties where coal was once king.

“We realize that we cannot leave these communities behind,” Anderson maintained.

Source: Platts