Record gas prices have sparked panic in Europe and left policymakers scrambling for answers. Solutions—like bailing out power suppliers, protecting vulnerable retail consumers with state subsidies, or pleading with Russia for more gas—just paper over the cracks. Building strategic gas reserves is a better long-term fix for price stability.

However, the European Commission thinks otherwise. Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson, speaking on Sept. 22, said “renewables offer the alternative to our dependence on imports of fossil fuels” in response to the tight gas market member states now face. Simson’s remarks came after the International Energy Agency implored Russia to increase supplies into the world’s third-largest combined economy, without mentioning inventories, or reserves.

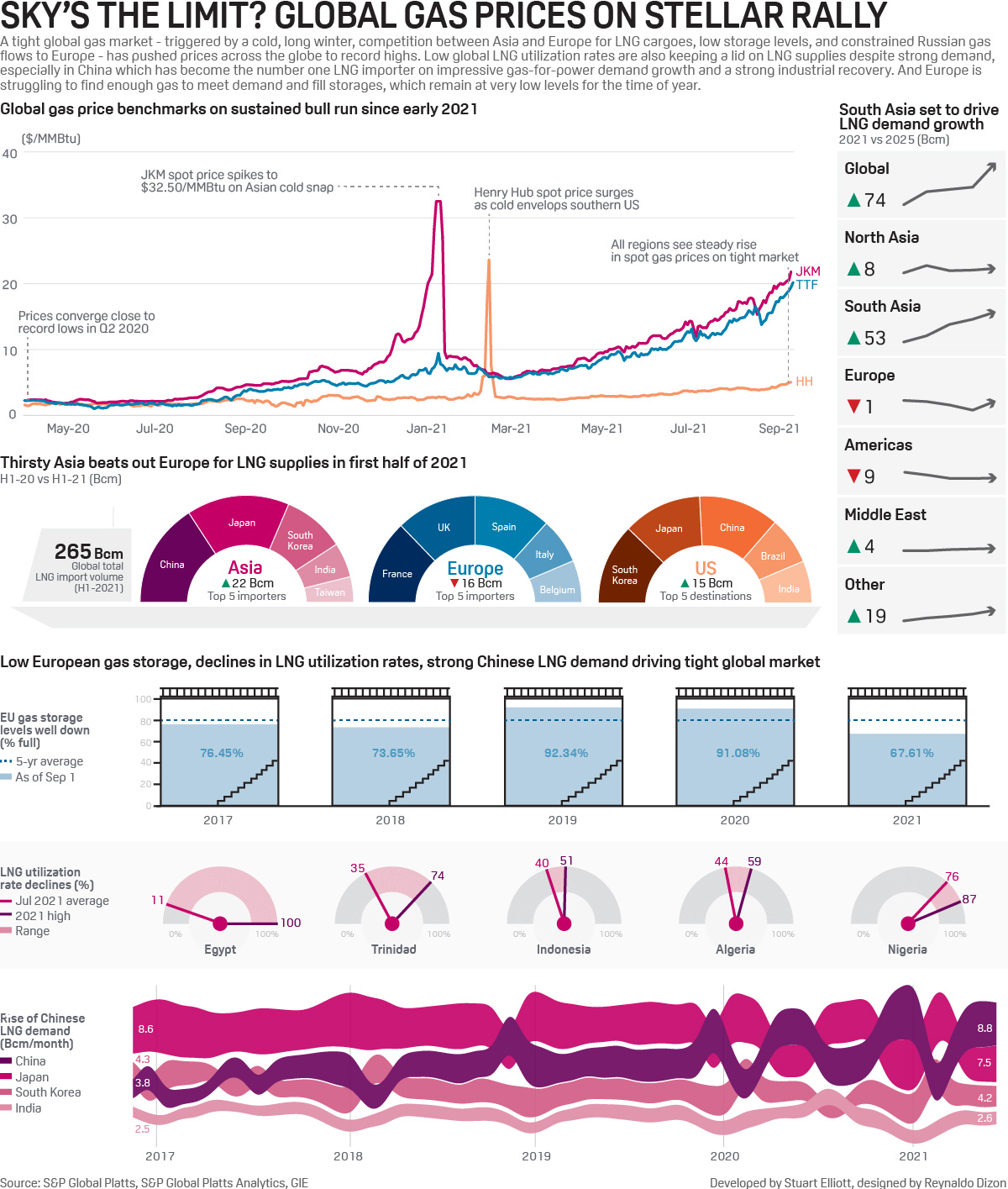

The panic has been caused by surging prices. S&P Global Platts assessed the Dutch TTF day-ahead natural gas contract Sept. 24 at Eur68.375/MWh, up from Eur11.40/MWh a year ago. International prices for liquefied natural gas are equally eye-watering. Platts JKM—the benchmark for spot-traded LNG delivered to Northeast Asia—was recently assessed above $28/MMBtu, a six-fold jump in a year.

Across Europe, gas markets have been squeezed in a vice. Russia is supplying lower volumes. Gazprom expects its sales in Europe and Turkey to total 183 Bcm in 2021, well down on its record peak of 201 Bcm in 2018. Is Moscow now following a value-over-volume strategy, holding back volumes to drive up the price? Such unilateral action is not out of the question in the absence of any form of global “Gas OPEC”, an idea floated a number of times without ever coming to fruition.

In the UK, a growing dependence on renewables hasn’t helped either. Lower-than-expected wind power output in September has forced the country’s network to increase gas generation and fire up coal plants to produce electricity.

“The whole market is dominated at the moment by a lack of inventory,” said Simon Thorne, global head of Generating Fuels and Electric Power at S&P Global Platts Analytics. “Europe is resolutely below the five-year average and this has taken any buffer out of the equation. The thing that isn’t being spoken about enough is stocks. There is no buffer and that has a profound impact on the market.”

Across Europe, levels of gas storage are down. Storage sites are 72% full, compared with inventory levels of 94% at the same time in 2020 across the 28-member group of nations. In the UK—which fully exited in the EU last year—closure of the Rough storage site in the North Sea in 2017 now looks premature, leaving the country with just seven relatively small commercial storage facilities.

‘Red herring’

Instead of infrastructure, the British government prefers to rely on a supply strategy dependent on the international market. The UK has domestic supply but is dependent on importing gas from diverse sources including Qatar, Nigeria, Norway, the US and interconnections with Europe, which in theory can import energy indirectly from Russia.

The result of the UK’s strategy and the various forces pressuring international energy markets has been a near 500% increase in domestic wholesale gas prices in the last year, forcing six small suppliers into bankruptcy and the government to subsidize the production of vital industrial gases to protect the economy and food supply chain. However, Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng has described the issue of storage as “a bit of a red herring.”

Still, the establishment of government-controlled strategic reserves of gas held in storage beyond existing commercially owned inventories could play an important role protecting countries like the UK from future price spikes. For example, the IEA requires its 30-member nations to hold the equivalent of 90-days oil imports in strategic reserve in case of unexpected supply shocks. No such policy exists for gas, which is dependent across Europe on commercial inventories and is at the mercy of foreign suppliers.

Several EU countries do have some regulation in the storage sector that requires minimum stocking levels, including Italy and France, but there is no centralized policy.

This reliance on imports can only increase with the opening of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. The 2,460 km-long two-string pipeline could still begin operations this year and will transport 55 Bcm/year of Russian gas into Germany and beyond. With much lower transit costs than via Ukraine, gas from the pipeline will be essential if Europe’s largest economy is to bridge the gap between renewables and fully phasing out its coal-fired power as part of the energy transition.

The US has used its Strategic Petroleum Reserve created by President Gerald Ford in 1975 to create a significant buffer. The SPR can hold over 700 million barrels of crude in its underground salt caverns. Earlier this month, China tapped its own strategic reserves of oil to dampen prices. India too maintains its own sizeable stockpiles of crude to be used in case of emergency.

Creating a similar system for gas to act as a strategic buffer, or a top-up to ensure commercial inventories are maintained above a five-year averages, is an idea worth considering.

Source: Platts