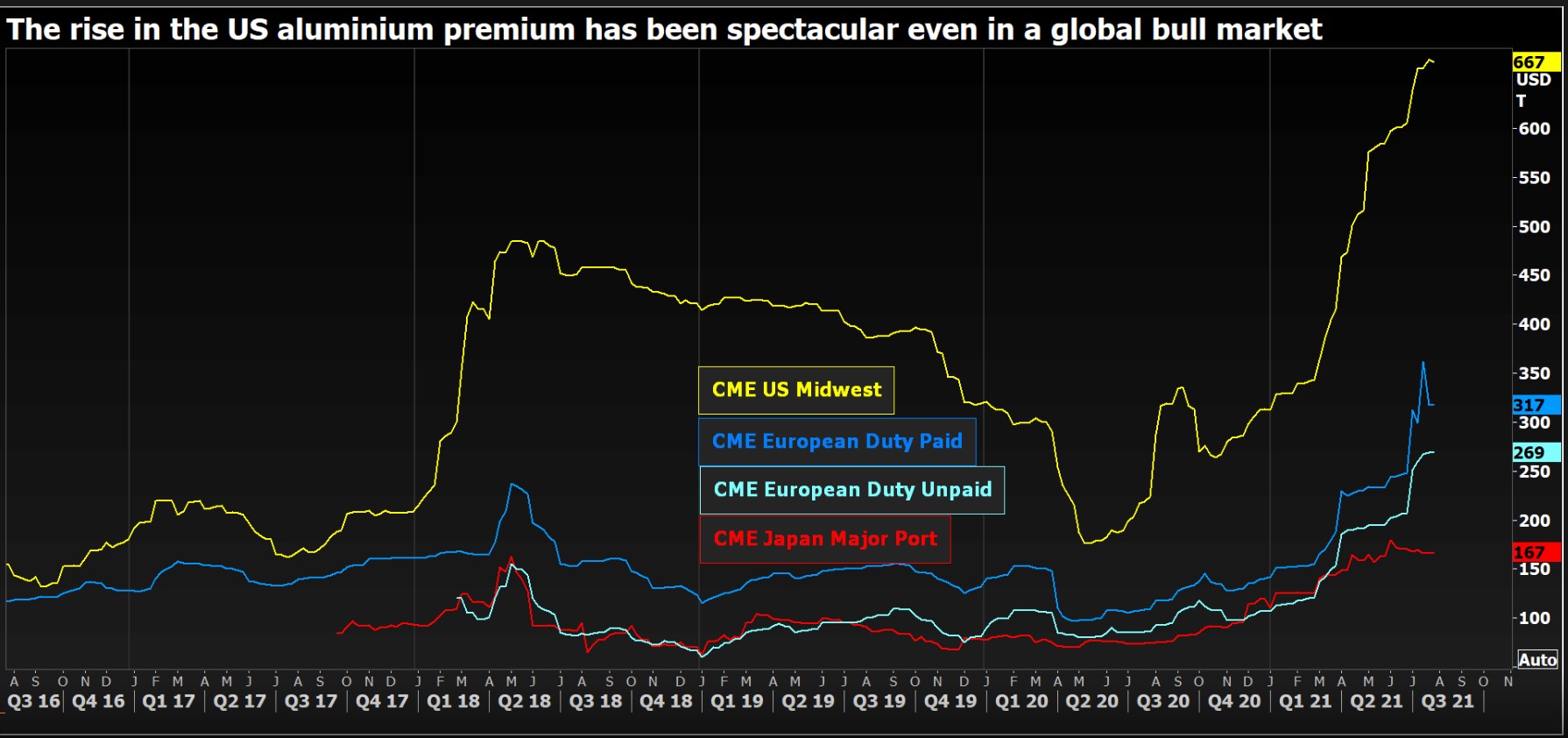

U.S. buyers of physical aluminium ingot are paying a record premium of 30 cents per lb, or $670 per tonne, to get metal to their plants.

The U.S. Midwest premium is payable on top of the London Metal Exchange (LME) cash price, which at a current $2,498 per tonne is within striking distance of May’s three-year high of $2,579.50.

The premium has never been higher.

Even the Trump Administration’s 2018 double-whammy of import tariffs and sanctions on Russian producer Rusal couldn’t push the premium beyond a May peak of $485 per tonne.

There are plenty of specific drivers at work in the North American aluminium market, but it’s not just aluminium buyers who are having to pay up.

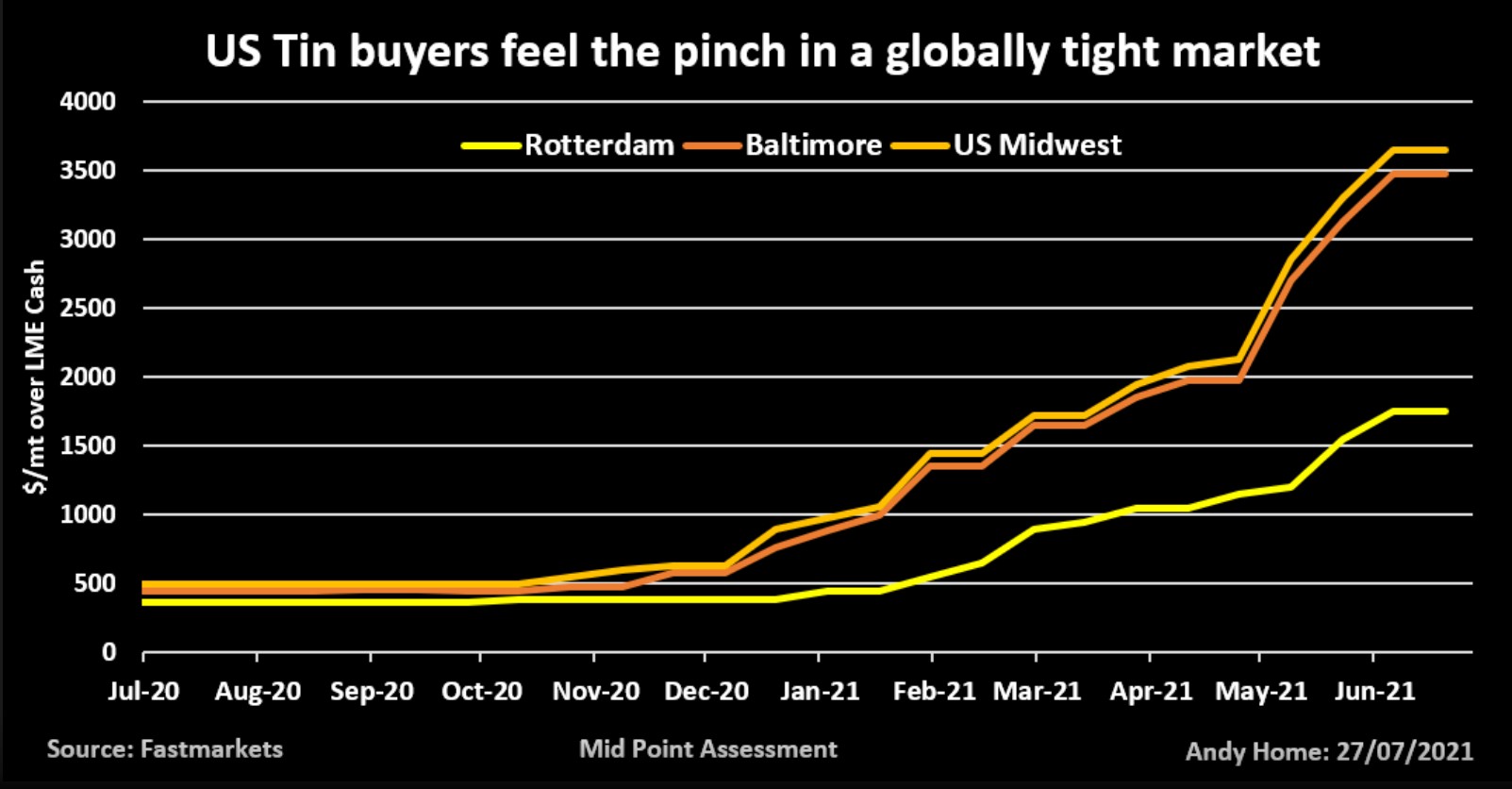

U.S. tin and lead buyers are also paying record premiums for their metal.

The common theme is one of import dependency, a vulnerability that is brutally exposed by chaos in the shipping sector that has disrupted everything from global automotive to local retail supply chains.

OUT OF STOCK

The United States has no primary tin or lead production capacity and imported 32,000 tonnes and 370,000 tonnes of refined metal last year respectively, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) found.

Tin imports accounted for around 75% of U.S. consumption last year and lead imports around 24%, lower because of the greater use of recyclable material in the all-important lead-acid battery sector.

Both tin and lead markets are experiencing global supply-side disruption.

The LME three-month tin price early on Tuesday hit a fresh all-time high of $34,990 per tonne on a combination of production hits and booming demand from the electronics sector.

LME tin inventory remains chronically low at just 1,165 tonnes, excluding the 1,150 tonnes scheduled for physical load-out. Most of those stocks – 1,080 tonnes – are located in Taiwan, close to Asia’s electronics hubs.

There is nothing at all in the United States, where Midwest buyers are now paying premiums of between $3,300 and $4,000 per tonne to get material, according to Fastmarkets’ assessments.

That, remember, is on top of the record LME price.

In a misfiring global tin supply chain, the U.S. finds itself at the back of the queue and facing the highest freight costs.

So too in the lead market, where Fastmarkets’ U.S. Midwest premiums have surged to record highs of up to 19 cents per lb over LME.

LME stocks of lead are also low and there is zero registered tonnage in the United States. Europe has stocks, but that market is still short of physical metal after Germany’s Berzelius Stolberg smelter was forced to close by last week’s flooding.

While the western lead market is caught in a rolling supply squeeze, the Chinese market is awash with the stuff. Lead stocks registered with the Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE) have grown from 45,900 tonnes at the end of December to 158,073 now.

There is an obvious arbitrage solution to this imbalance, but since the arbitrage will be with the LME, the bulk of any export shipments will likely head to exchange warehouses in Asia.

U.S. importers will still face high freight costs to move the metal to the domestic market, assuming there is available freight capacity.

GREATER COMPETITION

Record U.S. aluminium premiums were already adding to a potent mix of bull drivers before last weekend’s strike action at the Kitimat smelter over the border in Canada.

Rio Tinto, which operates the plant, has said it will reduce production to 35% of its 432,000-tonne per year capacity, tightening an already super-tight market.

Tariffs on U.S. imports have already served to reduce flows of Canadian metal and producers everywhere are ramping up output of value-added products, meaning less production of the commodity-grade metal that determines the Midwest premium.

More fundamentally, however, the U.S. aluminium sector faces greater competition for imported metal as China, the world’s largest producer, itself turns net importer.

Just about all of the LME inventory – both on- and off-warrant – is located at Asian locations, particularly Malaysia’s Port Klang.

Accessible stocks have migrated eastward to within easy shipping distance of China’s ports. Competition for this material and the associated higher freight costs are driving premiums higher in both the Europe and the United States, but particularly the latter because it is furthest away.

FRACTURING THE GLOBAL PRICE

U.S. nickel premiums are also starting to move sharply higher and copper shows signs of stirring.

Only zinc seems relatively immune because of greater domestic production capacity and plenty of LME stocks in New Orleans.

Stocks of everything else are in the wrong place as U.S. manufacturing recovers from the pandemic.

The current turmoil in the global freight sector has served to make the United States an island in metals supply chains, a phenomenon that becomes most acute when the global market is itself operating in supply deficit, as is the case with tin.

Such import dependency has led the Biden administration to initiate a supply-chain task force to build domestic resilience in everything from medical supplies to lithium-ion batteries.

Critical minerals are a central part of this initiative. Tin is one of them but tends to be overshadowed by rare earths and battery metals, the current focus of U.S. government minerals policy.

Lead isn’t on the list even though it powers most of the vehicles currently on U.S. roads.

And aluminium has been deemed critical for national defence, but the Trump solution of import tariffs has exacerbated the stellar rise in the premium cost to U.S. manufacturers.

Aluminium also reveals the longer-term issues facing U.S. metal buyers. The tariffs, which remain in place under Biden, have accentuated the very import dependence they were meant to alleviate, baking it into a structurally higher domestic premium.

Trying to reshore supply chains inevitably makes them less global. That increases the significance of regional pricing – premiums – over global pricing on the LME. Such seems to be the evolving trend in aluminium pricing.

The woes in the global shipping sector will eventually pass but this underlying shift in metals pricing in a deglobalising world may be here to stay.

Source: Reuters (Reporting by Andy Home; Editing by Barbara Lewis)